In 1970, roboticist Masahiro Mori coined the term “the uncanny valley” to describe when non-human objects become so life-like that it is unsettling, even repulsive. In “Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI” at the de Young Museum (through June 27), Claudia Schmuckli has curated a deeply provocative exhibition that moves beyond the superficial spectacle of technology to unveil the web of economic, social, and political interests underlying Artificial Intelligence.

With significant works by 14 prominent artists, the exhibition dives into many riveting dialogues, like the intersection and disruption of selfhood and AI through deep fakes; psychedelic drugs; the anxiety of racial identity in networked life; and animatronics that reveal the slippages and emissions of language regarding race and culture. Most poignantly, the exhibition reveals the intersection of AI and institutional power, in the form of predictive policing and the art world’s connection to a military manufacturer.

In Hito Steyerl’s “The City of Broken Windows” (2018), the artist explores broken windows as an indicator of crime. On one end of the room-sized installation, the artist presents a video of engineers breaking glass to design an alarm system that uses AI to identify security breaches. Juxtaposed on the other end of the room, a video features community organizers that paint flowers on the plywood covering broken windows to heal low-income communities.

Beginning in the 1980s, with highly biased and unconstitutional tactics like “Stop-and-Frisk,” Broken Windows Policing targeted minor offenses in largely minority communities to prevent the escalation of crime. As AI is used to build alarm systems, it attempts to secure the safety and property of certain groups, presumably those with means, while neglecting the harm done to communities who endure Broken Windows Policing.

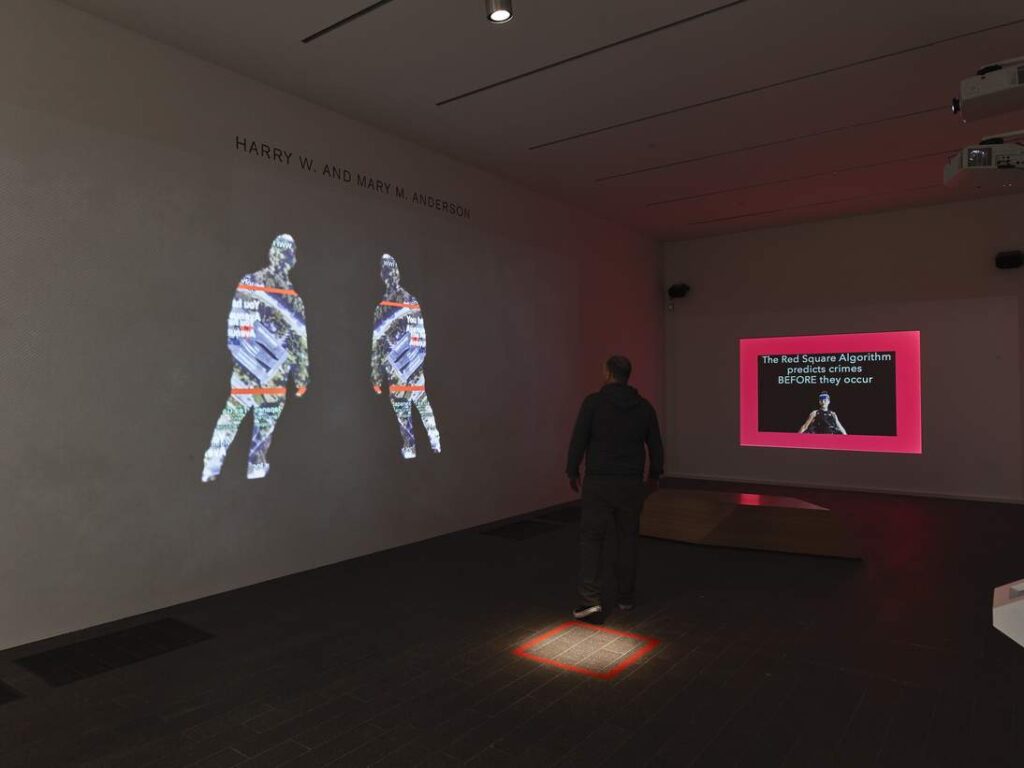

As AI has moved into predictive policing, Lynn Hershman Leeson’s “ShadowStalker” (2019) invites viewers to seize control of their location data by revealing their digital trails, one of the data sets used to train AI. Most poignantly, the video features a monologue by Tessa Thompson, from the HBO science fiction series “Westworld” (2016-present). Thompson explains how the predictive policing company PredPol tracks personal data, which has become more valuable than oil. Moreover, as red squares on maps indicate areas of high risk and operate as an icon for one’s location, the red square is a prison and a place for revolution.

As Hershman Leeson’s red square indicates high risk zones, Forensic Architecture’s “Triple-Chaser” (2019) employs yellow squares to signify image recognition of perilous objects. The collaborative artist team responded to their invitation to be included in the 2019 Whitney Biennial by tracking the Whitney Museum’s own connection to the arms trade. In addition to owning Safariland Group, a manufacturer of military supplies and tear gas, Warren B. Kanders sat as vice chair of the museum’s board of trustees.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

The video chronicles how Forensic Architecture built a machine-learning algorithm to identify Safariland Triple-Chaser tear gas grenades based on CGI modeling and video and photographs of actual canisters from around the world, including Tijuana and Gaza. As corporations and governments track individuals, Forensic Architecture turns the tables to reveal the reach of these parties as they attempt to squash protest, which implicates the art world.

While Silicone Valley touts smart technologies for their conveniences, these algorithms are subject to government and corporate biases and interests. As communities around the US have protested for policing reform, “Uncanny Valley” reveals technology’s ties to oppressive tactics and positions individuals and artists as active agents in securing our own digital trails, neighborhoods, and holding the art world accountable.

As one the most probing media-based exhibition that I have seen in many years, “Uncanny Valley” should go on to be one of the seminal exhibition that captures this political, social, and technological moment.

“Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI“ runs though June 27 at the de Young Museum.